The Ultimate AI Humanizer Showdown:

Grammarly vs. QuillBot vs. VerbEdit

Tired of your AI-generated text getting flagged? Worried your writing sounds robotic? In the world of AI writing assistants, the ultimate test is no longer just about grammar or clarity; it's about authenticity. The critical question for students, marketers, and creators is: which AI paraphrasing tool can produce genuinely human-like writing that reliably bypasses AI detection?

Forget the marketing hype. This is a direct, data-driven showdown. We've fed identical text passages into Grammarly, QuillBot, and VerbEdit to see what comes out the other side.

For each round, you're in the driver's seat. Read the anonymous outputs, vote for the one that sounds the most natural, and then we'll pull back the curtain to reveal the AI detection scores.

Rules of Engagement

To ensure fairness, we locked in standardized settings. QuillBot and VerbEdit used Standard Mode. Grammarly used its default rewrite function. Crucially, each sentence was processed only once—no cherry-picking results.

Simple Text Paraphrasing

"Thanks to rapid progress in artificial intelligence, we have entered an era when technology and philosophy intersect in interesting ways. Sitting squarely at the centre of this intersection are large language models (LLMs). The more adept LLMs become at mimicking human language, the more vulnerable we become to anthropomorphism..."

Which version sounds most human?

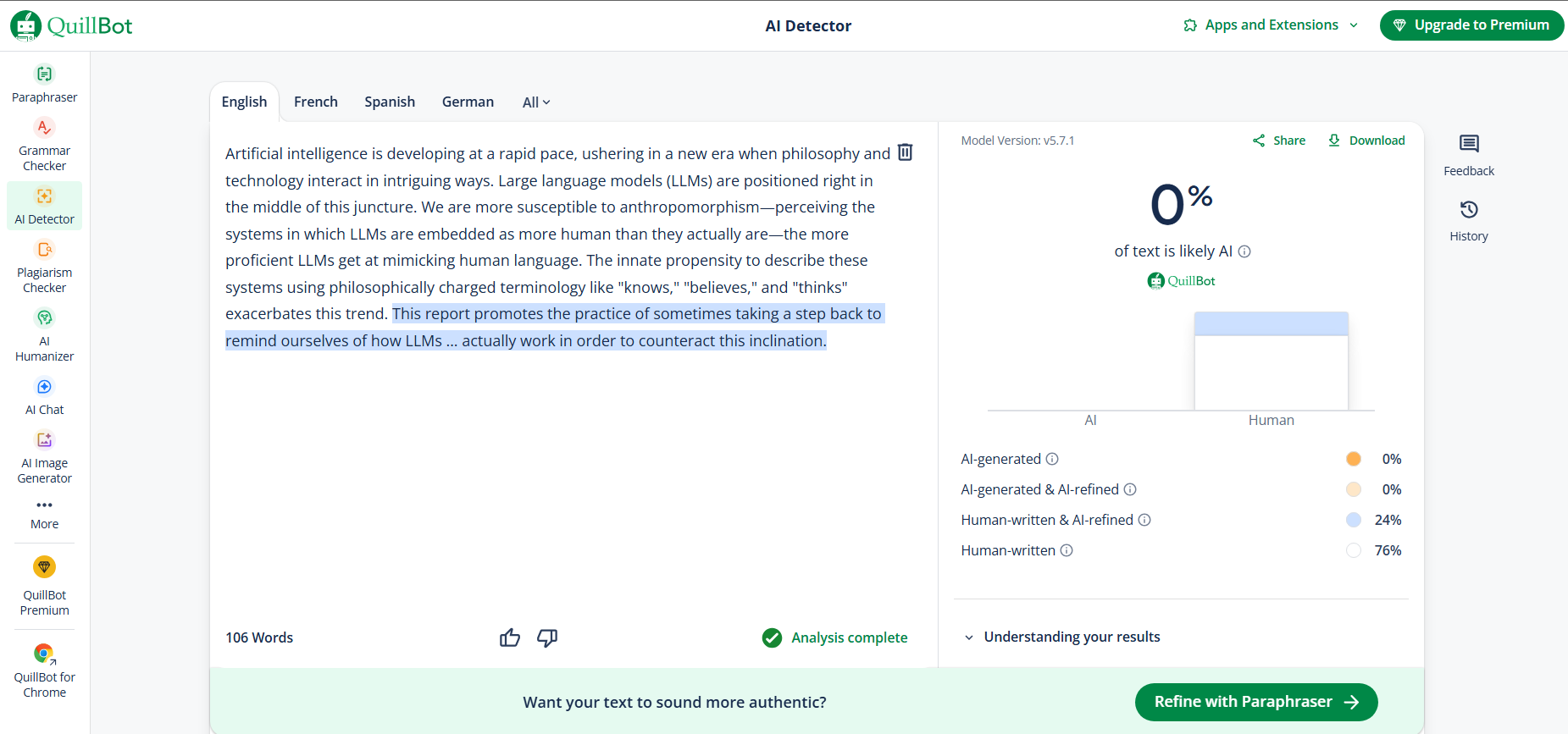

Artificial intelligence is developing at a rapid pace, ushering in a new era when philosophy and technology interact in intriguing ways. Large language models (LLMs) are positioned right in the middle of this juncture...

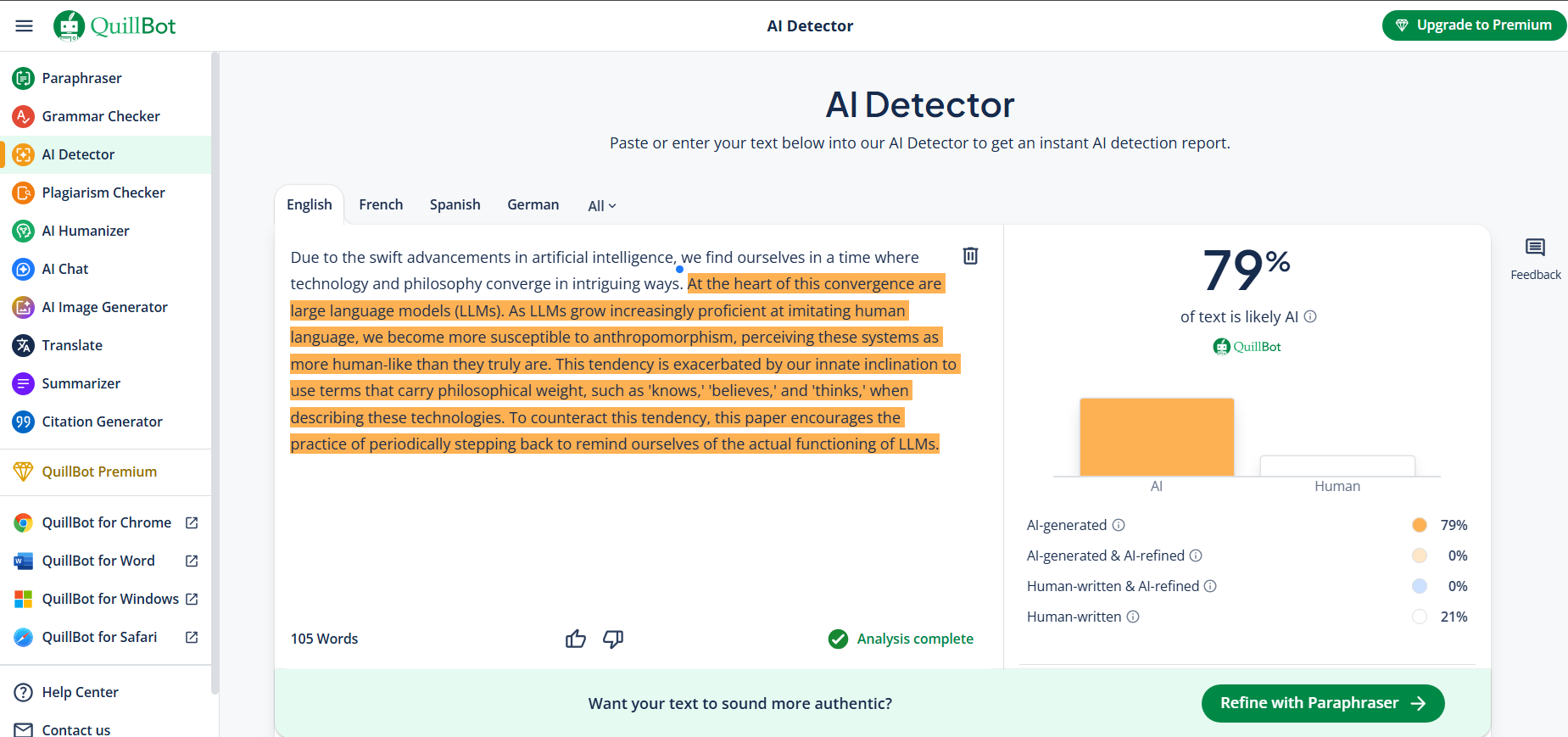

Due to the swift advancements in artificial intelligence, we find ourselves in a time where technology and philosophy converge in intriguing ways. At the heart of this convergence are large language models (LLMs)...

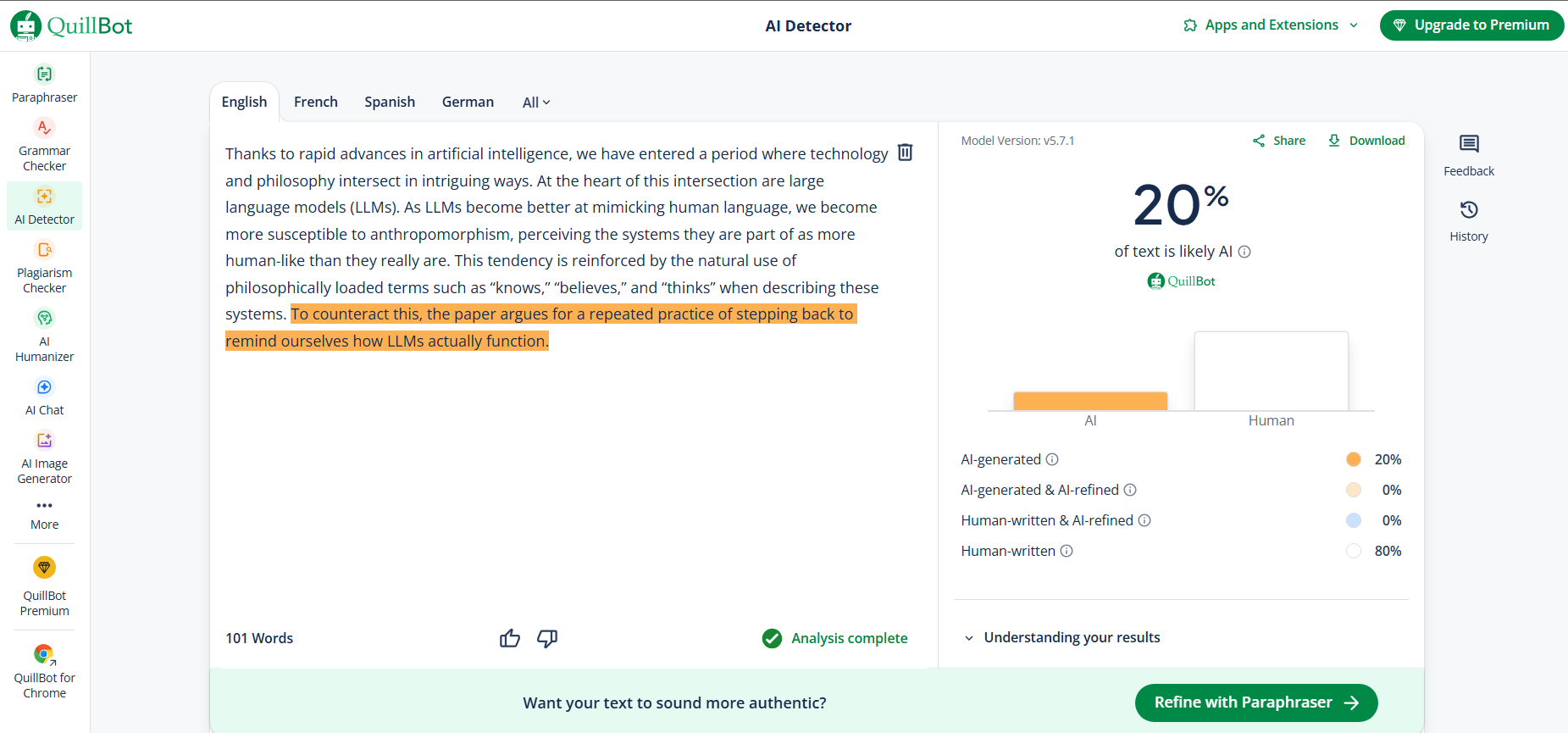

Thanks to rapid advances in artificial intelligence, we have entered a period where technology and philosophy intersect in intriguing ways. At the heart of this intersection are large language models (LLMs)...

Round 1 Analysis

In our first round, every tool successfully rephrased the text. The real story is the AI detection scores. One output was flagged as 100% AI, while others scored much more human. The more an AI changes sentence structure unpredictably, the better it evades detection.

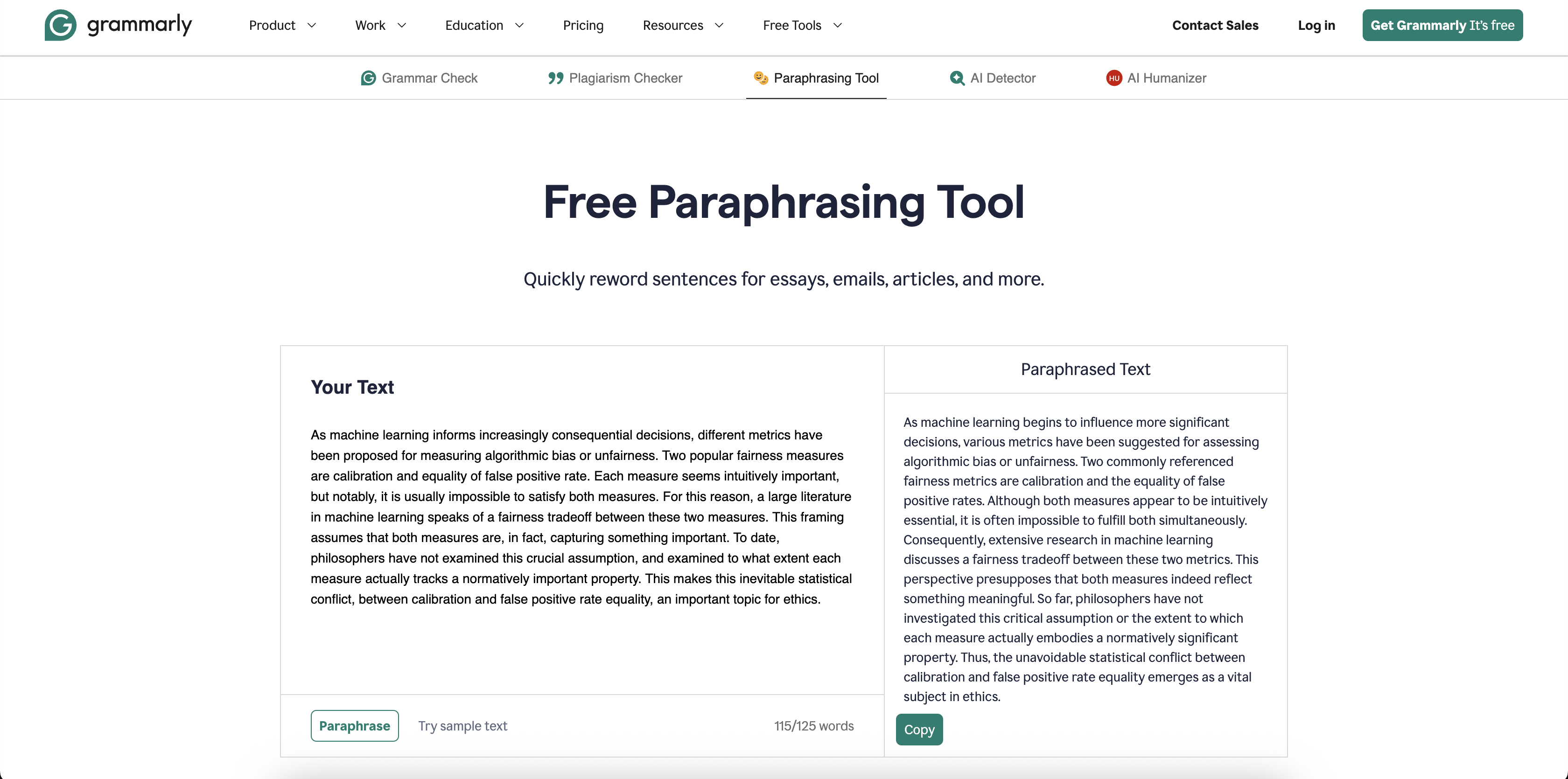

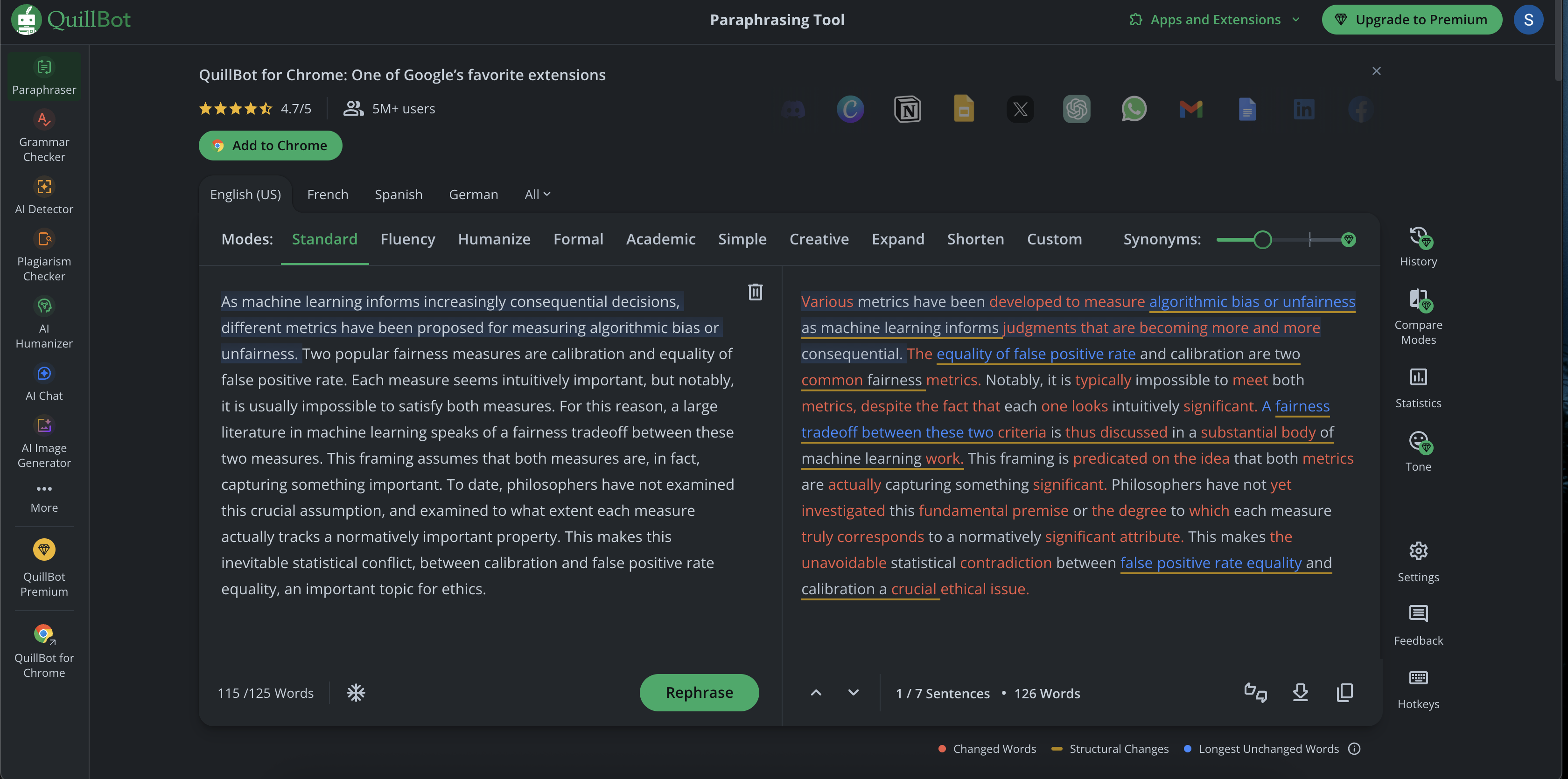

Abstract Concepts & Nuance

"As machine learning informs increasingly consequential decisions, different metrics have been proposed for measuring algorithmic bias or unfairness. Two popular fairness measures are calibration and equality of false positive rate..."

Vote: Which AI preserves complex meaning?

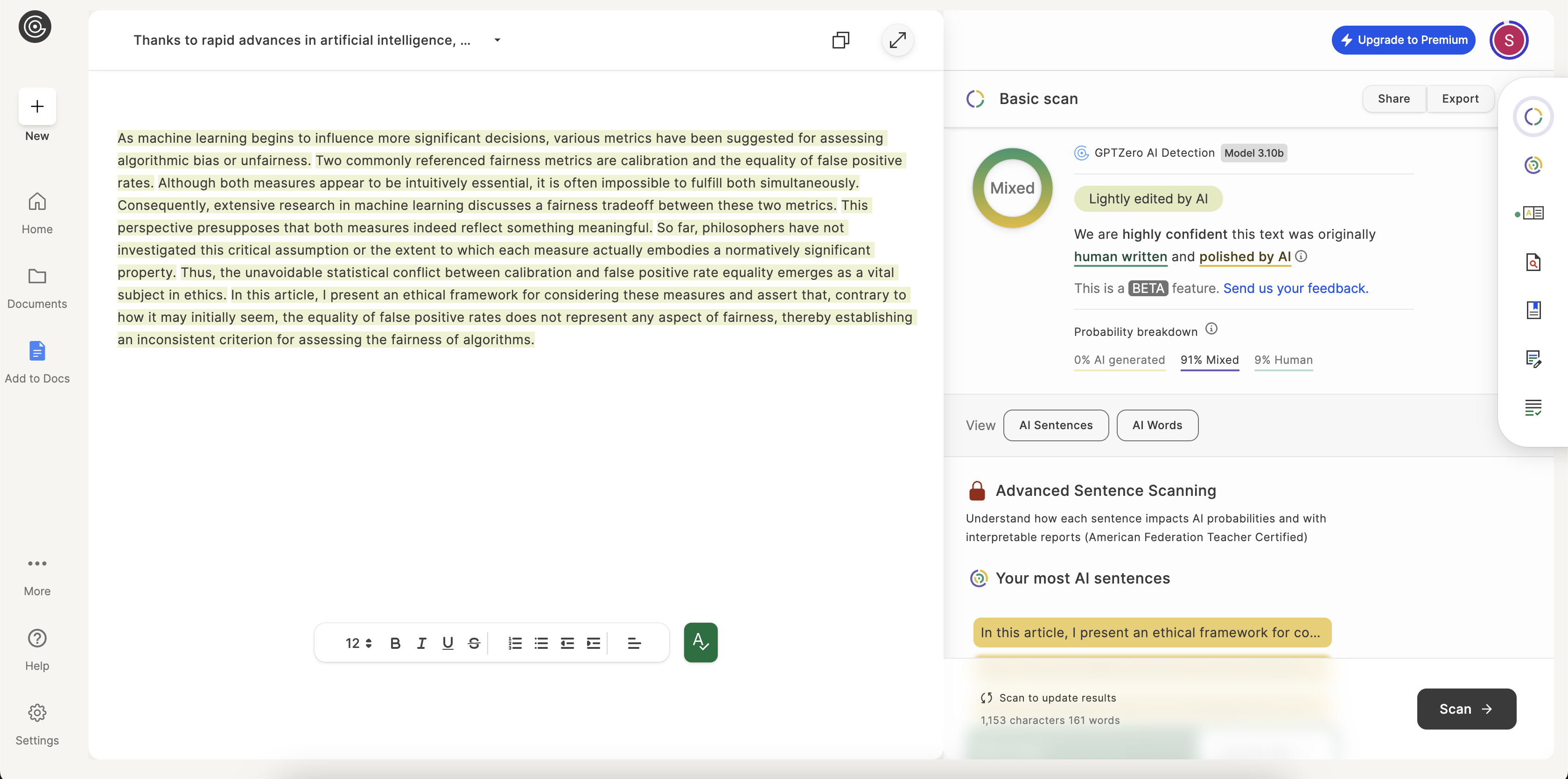

As machine learning begins to influence more significant decisions, various metrics have been suggested for assessing algorithmic bias or unfairness...

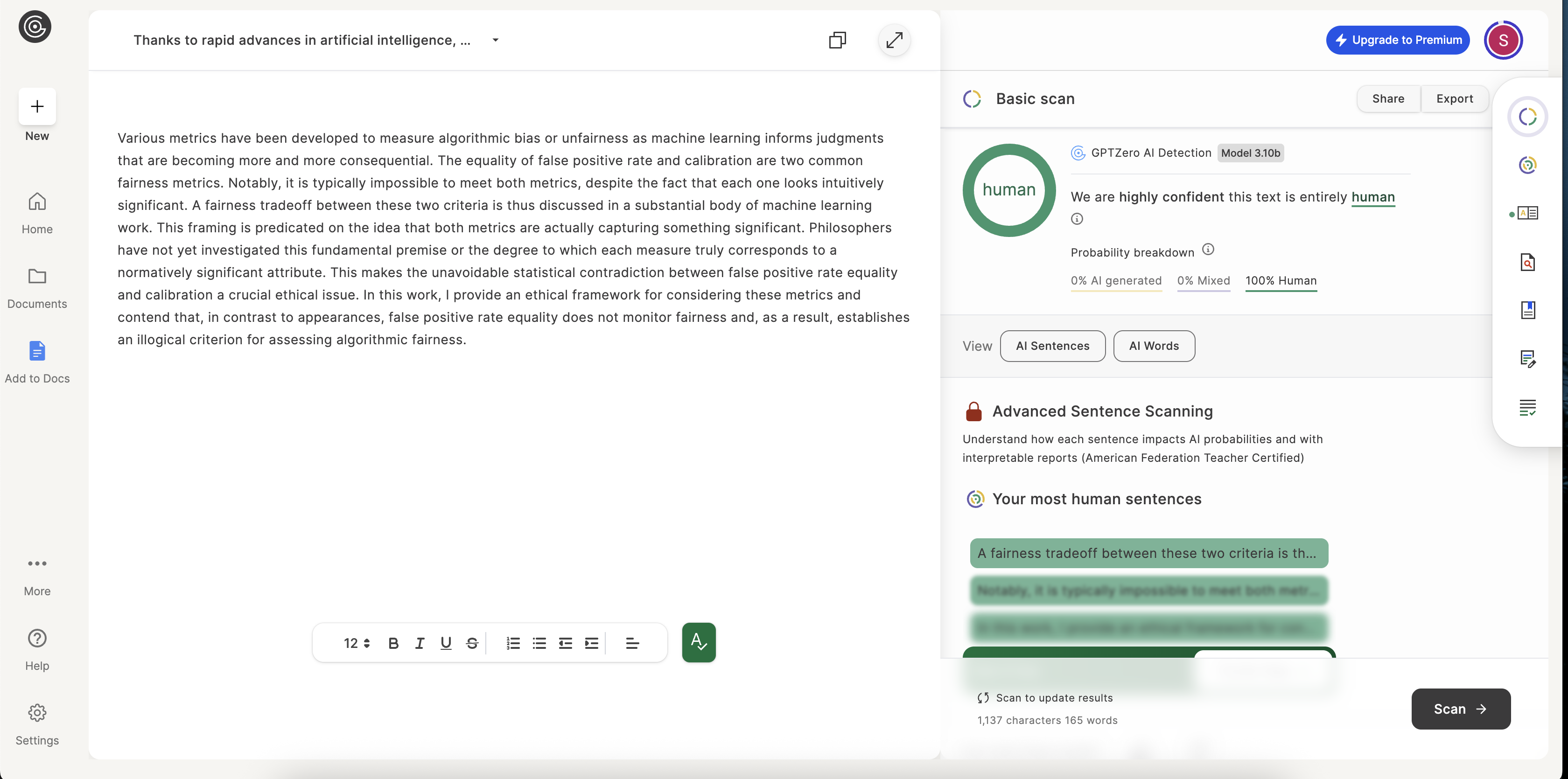

Various metrics have been developed to measure algorithmic bias or unfairness as machine learning informs judgments that are becoming more and more consequential...

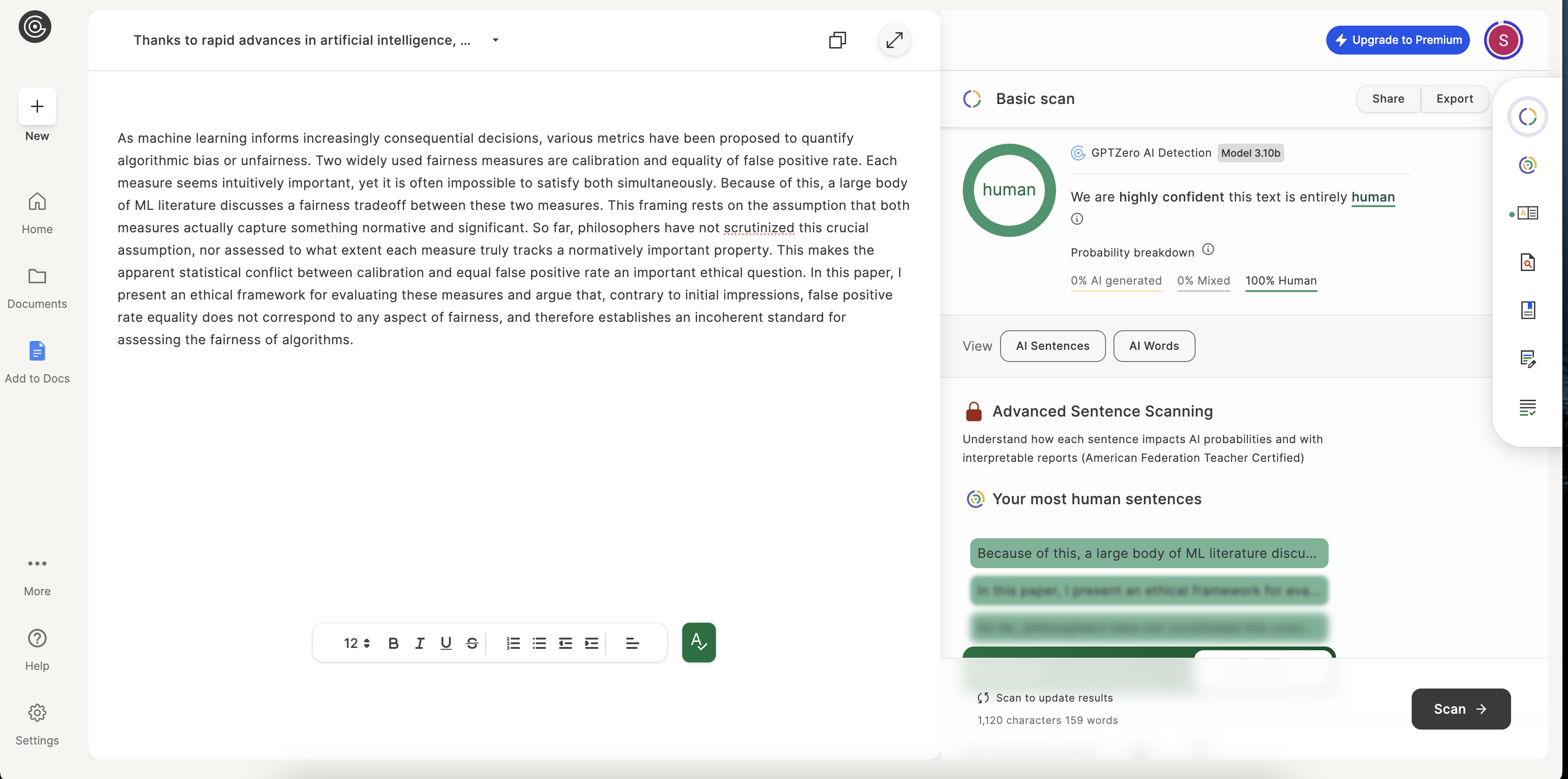

As machine learning informs increasingly consequential decisions, various metrics have been proposed to quantify algorithmic bias or unfairness...

Round 2 Analysis

With more complex, layered concepts, the true colors of each AI tool begin to show. The task here isn't just to rephrase words but to maintain the delicate logical connections between ideas. VerbEdit's output was rated 100% human by both detectors, indicating its strength in preserving the academic tone.

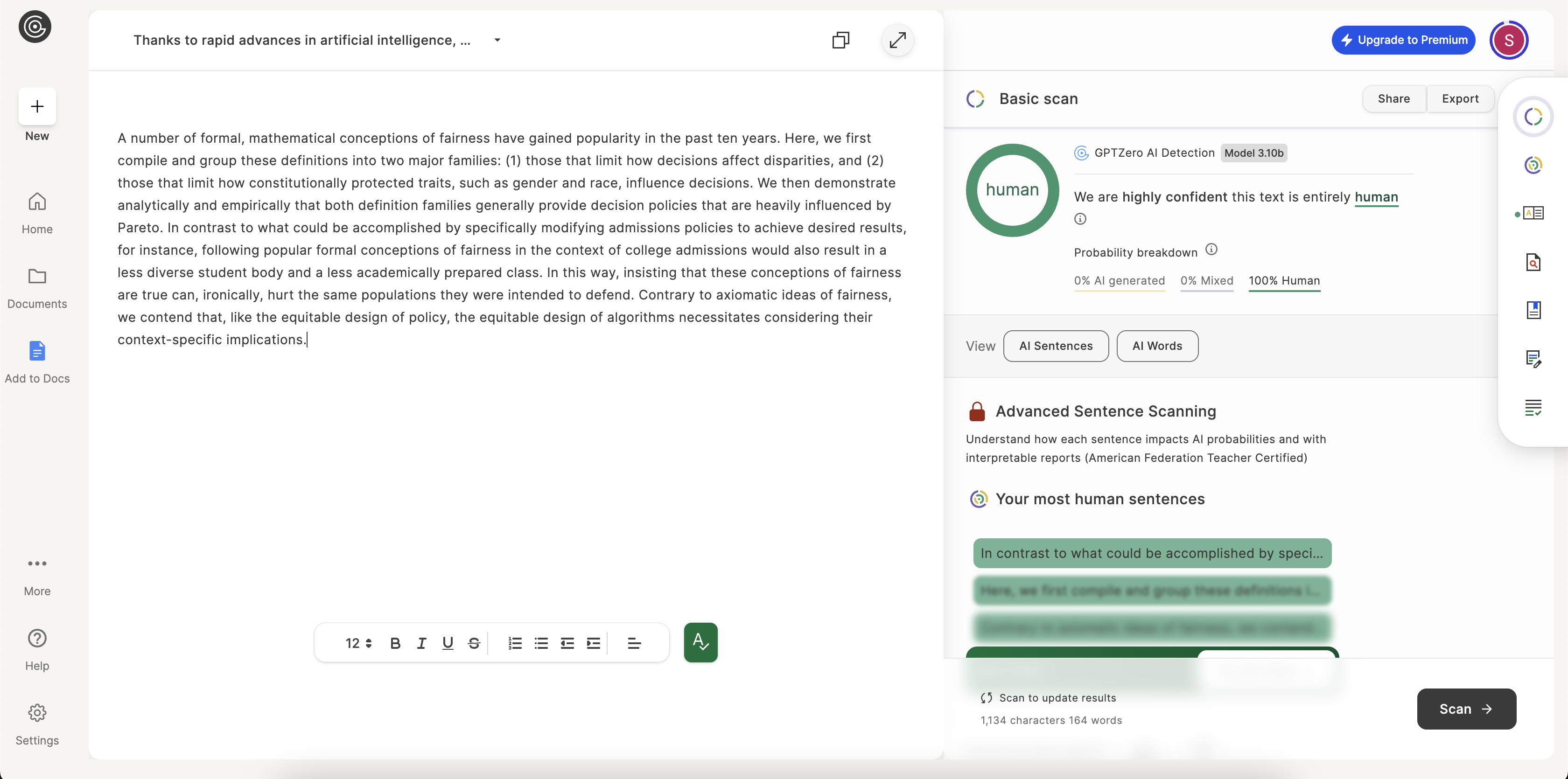

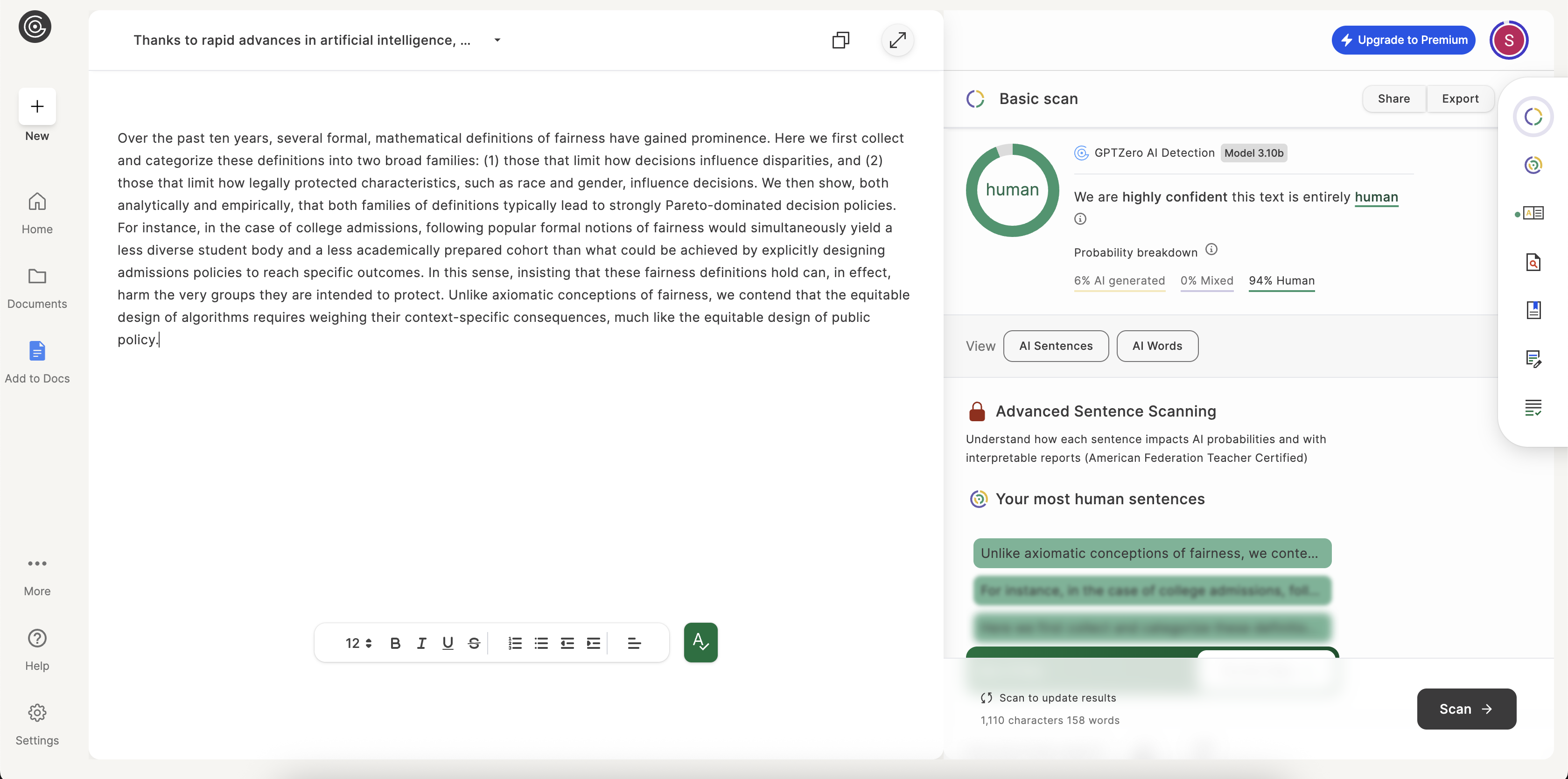

Advanced Academic Text

"Over the last decade, several formal, mathematical definitions of fairness have gained prominence. Here we first assemble and categorize these definitions into two broad families: (1) those that constrain the effects of decisions on disparities..."

Final Vote: The toughest challenge.

Over the past ten years, several formal, mathematical definitions of fairness have gained prominence. Here we first collect and categorize these definitions into two broad families...

A number of formal, mathematical conceptions of fairness have gained popularity in the past ten years. Here, we first compile and group these definitions into two major families...

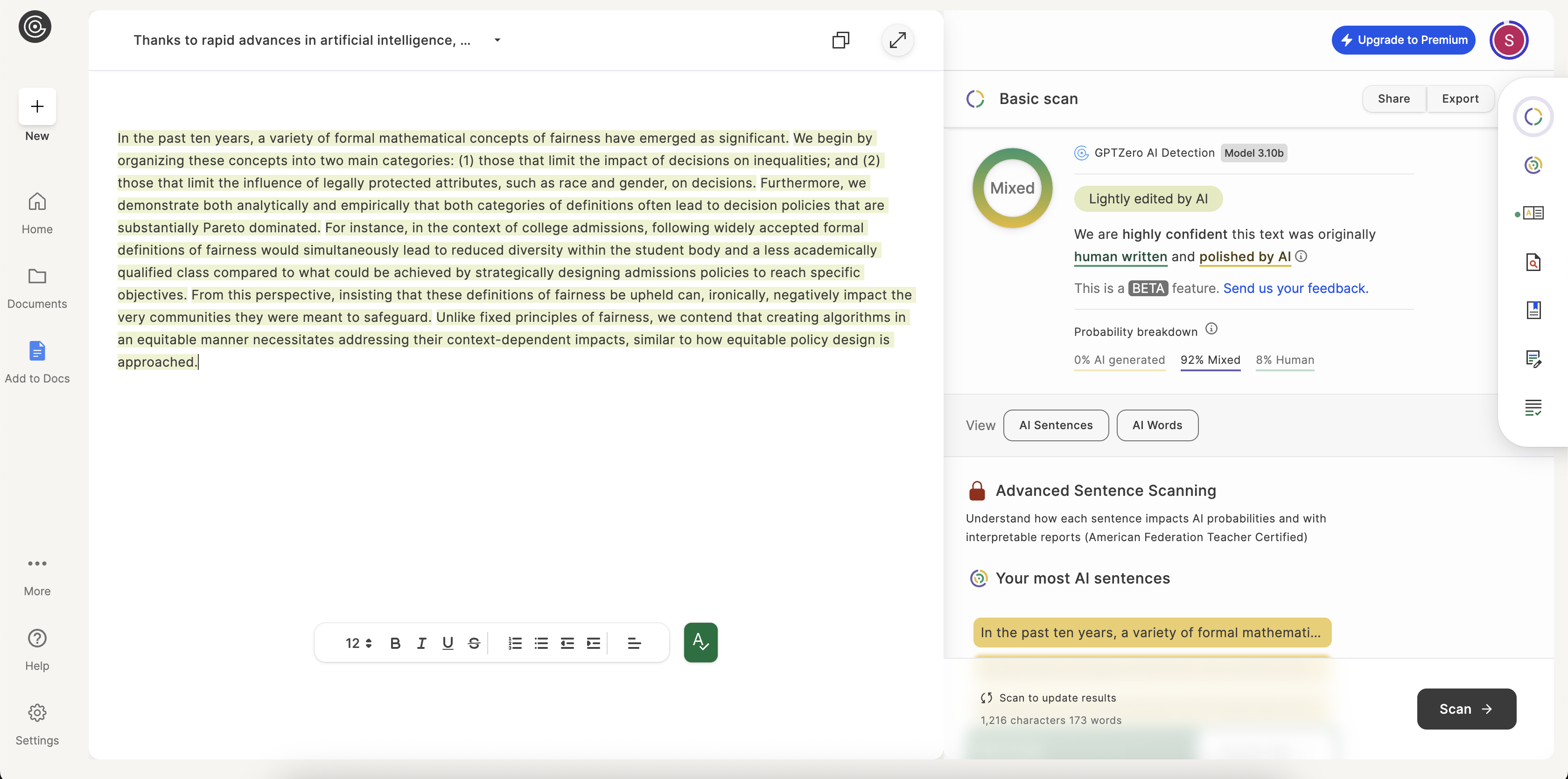

In the past ten years, a variety of formal mathematical concepts of fairness have emerged as significant. We begin by organizing these concepts into two main categories...

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the best AI rewriter to avoid detection?

Based on our tests, tools that prioritize nuanced changes over aggressive restructuring, like VerbEdit, tend to produce text with lower AI detection scores.

Can AI detectors be 100% accurate?

No, AI detectors are not infallible. They work by recognizing patterns common in AI-generated text. A '100% Human' score means the detector found no AI patterns, but it's not a guarantee.

Is QuillBot or Grammarly better for paraphrasing?

It depends on your goal. QuillBot is designed specifically for paraphrasing and offers aggressive options. Grammarly's rewriting feature focuses more on clarity. For a distinct rewrite, QuillBot is generally more powerful.

Final Verdict

The "best" tool depends on your goal. If you need clean, professional grammar correction, Grammarly is excellent. If you need aggressive rewriting, QuillBot is powerful. However, for nuanced humanization that retains academic tone while lowering AI detection scores, VerbEdit proved highly effective.

| Tool | Strength | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | Grammar & Clarity | Professional editing & polish |

| QuillBot | Restructuring | Changing sentence structure |

| VerbEdit | Human Nuance | Bypassing AI detection |

Data & Source Screenshots

Transparency is everything. Here are the unedited screenshots from the AI detection tools used in our analysis.

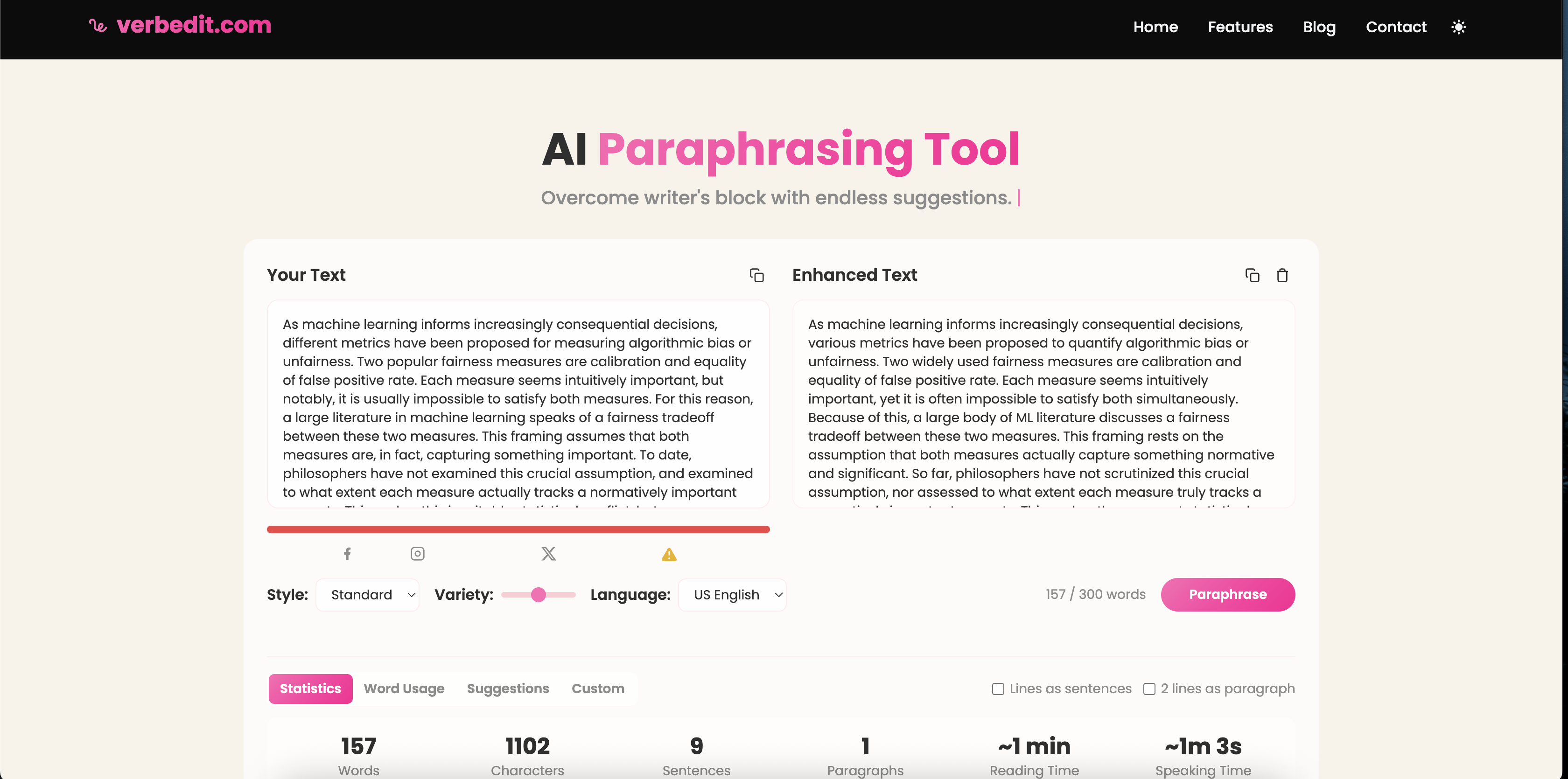

Try the Paraphraser

See the difference for yourself. Use VerbEdit to rewrite your text now.

Start Paraphrasing